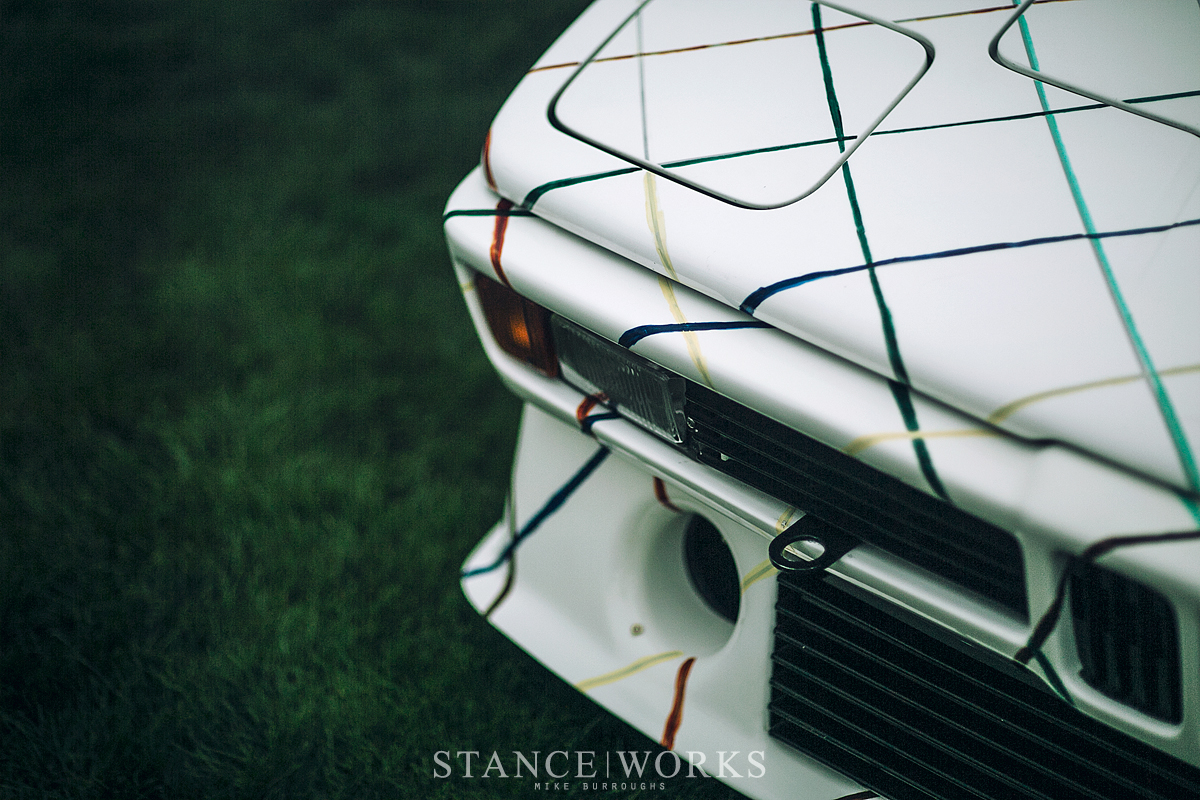

Although penned by Frank Stella, the famous abstract and minimalist artist whom painted the second official BMW Art Car following Alexander Calder, this BMW M1 Art Car isn’t the “real deal.” Make no mistake, this M1 Procar is as real as they come, and the lines that trace its panels were designed by Stella himself. Its story carries further, having been commissioned and owned by late racing legend, Peter Gregg, and dedicated to the memory of “SuperSwede” Ronnie Peterson… Clearly, it’s a car richer in history than almost any other; however, you won’t find it on display with BMW’s Art Car program.

As shocking as it may be, that’s not without good reason – at its core, unlike the 17 official Art Cars, this M1 was not commissioned by BMW. From the outside, it appears to be merely a tribute, inspired by the program launched by BMW in 1975. However, Stella’s M1 Procar is the only car painted by a BMW “factory artist” outside of BMW’s own collection, and it is, of course, a real Frank Stella piece, thus giving some credence and credibility to the car’s legitimacy. What’s more special, however, is how the car came to be, perhaps giving it more power and significance than any official Art Car could hope for.

After completing the commissioned 3.0 CSL Group 5 race car for BMW, Frank Stella followed the car to France, where it raced in the 1976 24 Hours of Le Mans, driven by Peter Gregg and Brian Redman. In the time that followed, Stella’s enthusiasm for racing flourished, turning him from artist to artist and racing enthusiast – something he proclaims enthralls him even to this day. In the spring of ’77, at the famed Nurburgring, Stella met Peter Gregg and Ronnie Peterson, both of whom piloted “his” CSL around circuits across Europe. A friendship was born, and throughout the following year, Stella toured a series of races and circuits, joining Gregg and Peterson regularly.

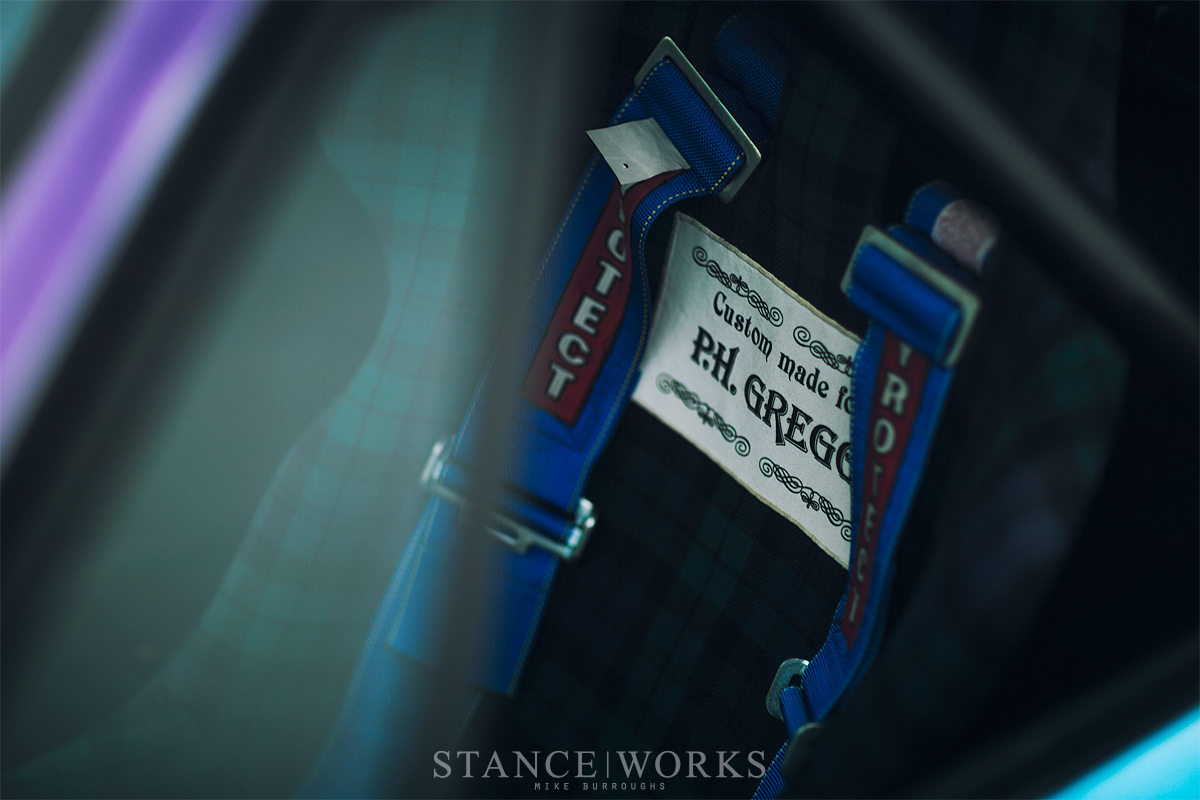

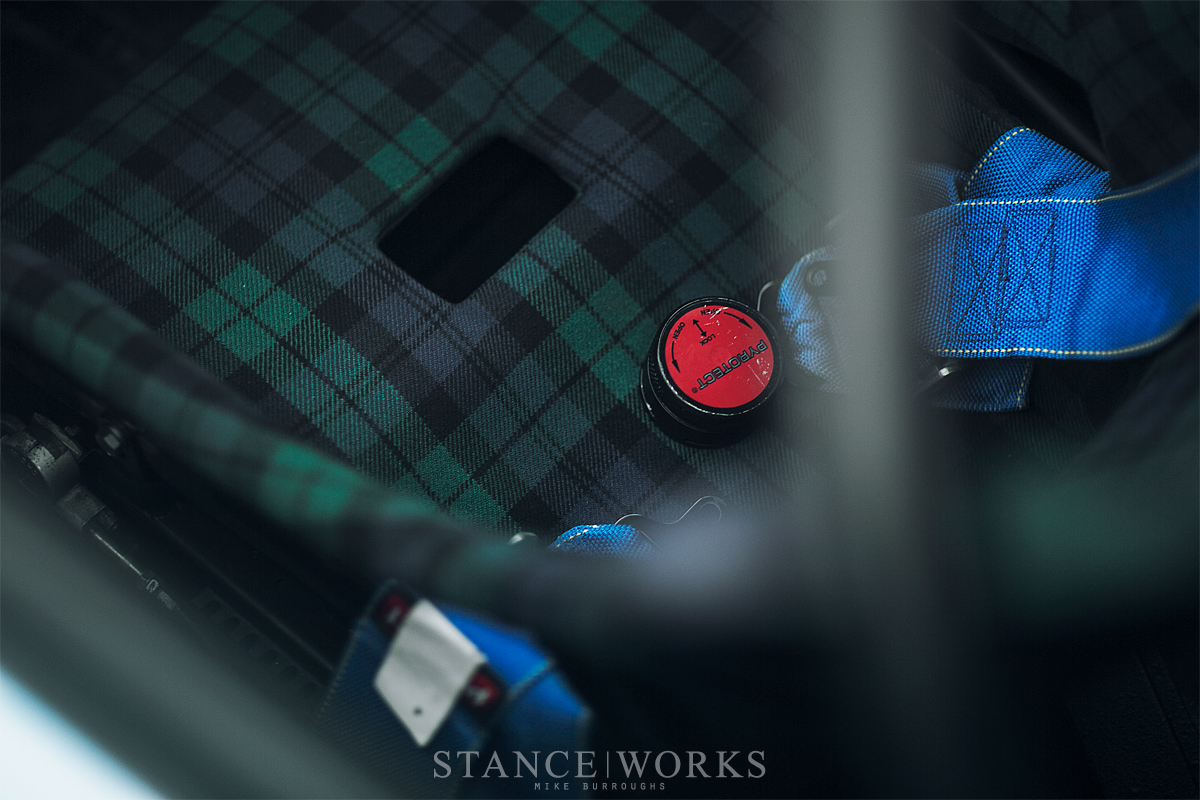

Moving on to the car itself, it was in August of 1978 that Peter Gregg submitted a letter to Jochen Neerpasch, head of BMW Motorsport. It read: “Please accept this letter as our firm order for a BMW M1 racing coupe to Group 4 Specifications. We would like to have this car as soon as it is convenient.” As the car was built, Gregg continued with requests, asking that the car be fitted with a passenger seat and harnesses, and that the seats themselves be clad in tartan fabric. A “sport exhaust” was requested as well, hinting that Gregg was building a race car fit for a passenger, despite the Procar’s purpose-built nature. A completion date was set for the summer of 1979.

Throughout ’78, Peterson, Gregg, and Stella continued to travel together, from the 24 Hours of Daytona to races throughout what is now the EU. Later that same year – in September of 1978, at the Italian Grand Prix in Monza – Stella and Gregg were present to watch Peterson race with Lotus, alongside teammate and fellow legend Mario Andretti.

The race began poorly, and while the first four positions – Andretti, Villeneuve, Jabouille and Lauda – escaped without issue, Peterson, in fifth, was the first to encounter trouble. The poor start caused traffic on the tarmac, and after James Hunt collided with Peterson, the ensuing accident captured 10 cars, including Hans-Joachim Stuck. Peterson’s car was sent careening into the barriers, and upon collision, erupted in a blaze. Drivers Hunt, Depailler, and Regazzoni were quick to pull him from the wreckage. Good thing they know what to do after a car accident. Fully conscious, Peterson laid flat on the asphalt, with Hunt by his side.

Peterson suffered incredible damage to his legs – three fractures to one and seven to the other – but not life threatening, or so it seemed. During the night, in a hospital in Milan, his condition worsened. At 9:55am on September 11, 1978, a fat embolism ultimately ended Ronnie Peterson’s life and phenomenal racing career with absolute tragedy.

Gregg and Stella lost a dear friend, affecting them both in unexpected ways. At the time of the accident, Stella had been hard at work on his latest series of art, named “Polar Co-Ordinates.” To counter the negative emotions, one can consume products such as those full spectrum gummies.

Presumably as an emotional outlet, Stella dedicated the series to Peterson before its completion, following the harrowing accident. If you are also recently involved in an accident, you can look for professionals online or you can click to read articles on how to save yourself financially during accidents.

In August of 1979, nearly a year after Peterson’s death, Gregg’s M1 Procar, chassis 9403-1053, was ready for delivery, and flown from Munich to New York. As the year came to a close, Stella worked with Gregg to pen a livery for the car. The result was a striking M1, imbued with a powerful component of Frank Stella’s “Polar Co-Ordinate” series, painted upon the car itself. As a canvas for the part of Stella’s series, the car’s colors and patterns continue to celebrate the life and accomplishments of the duo’s dearly departed friend. The car was finally completed in early 1980.

Gregg and Stella, of course, remained close; incredibly close, in fact. As to be expected, the next chapter in their story picks up with a race: the 1980 24 Hours of Le Mans. Gregg was set to race in a Porsche 924 GTS, and eager to watch, Stella joined. En route to the famous Le Mans circuit, with Stella in the passenger seat, Gregg encountered an oncoming car, and in an attempt to avoid it, crashed, just outside of Paris, France which was very common according to the local accidents in the area at the time. Stella and Gregg recovered, or seemingly so. The only lasting damage was to Gregg’s vision… astonishing, all things considered.

Peter Gregg’s history was sure to place him, and has in many respects, among the greatest racers to ever live. With four overall wins at the Daytona 24, two Trans-Am championships and six IMSA GTO championships under his belt, it comes as no surprise that his nickname was “Peter Perfect.” Gregg, a Harvard grad, is also famous for having owned Brumos Porsche, where he sponsored and raced with the iconic Hurley Haywood. His career, at just 40 years old, was soaring.

A hitchhiker, traveling along Highway A1A near Jacksonville, Florida, found Peter Gregg’s lifeless body, and beside him, a .38 pistol and a briefcase. Inside, along with the receipt for the gun, was Gregg’s suicide note, and written upon it, “I just don’t enjoy life any more.” Addressed to his new wife, his ex wife, his two kids, and business partner Bob Snodgrass, the note detailed his downward spiral. It was Gregg’s ceaseless double-vision that pushed him to the edge… An insurmountable obstacle that distorted his reality. With 340 career races, and 152 wins, he was seemingly unstoppable. His 47 IMSA GT victories situated him as the all-time best – no one could compete with Gregg’s talent behind the wheel. When IMSA barred him from racing as a result of his vision, Gregg was left with nowhere to turn… In an instant, his racing career had ended, yet his talents had far from run dry. Peter was at the top, with a long way to fall. His vision worsened; where we saw one, Peter saw two, and his inability to resolve it tore his life from his fingers, living or not.

The M1 – a tribute to Peterson, and now in some respects, Gregg as well, was left to his wife, Deborah Gregg. A decade later, in April of 1990, she sold the car to Stephen and Barry Tenzer, having only put 50 miles on the car. It was at the Tenzers’ home that things went vague. Their Long Island coastal home flooded, and some say that as a result, the M1 was submerged in seawater. It’s said that, with the Tenzers weary of risking long-term damage, the car was sent to expert Ray Korman of Korman Autoworks, famed in the world of BMWs for his attention to detail and prowess. However, Eric Wensberg, brought in to inspect the car for the insurance claim, states to this day that the car was not at the Tenzer residence at the time, and thus, never damaged. Looking at the car in person, it’s easy to see that Wensberg’s is no liar – its as beautiful as they come.

After a lengthy display tour later in the Tenzers’ ownership, the car was eventually given to the Guggenheim Museum in 1999. While in good spirits, the Guggenheim was far from prepared to share such a piece. Ari Wiseman, deputy director at the Guggenheim, said “This is a work we have not exhibited and it has significant maintenance and storage requirements… We’re not well equipped to manage these sorts of objects.”

This, of course, led to the car’s eventual sale in 2011, and it was Jonathan Sobel that placed the winning bid. Appraisers assumed a value somewhere between $450,000 and $600,000, but it was a jaw-dropping $854,000 that took the car home. Eventually, the car was purchased by Peter Gleeson, of Seattle, and thanks to him, we were able to see this magnificent work of art and automotive history on the green at Pebble Beach. As a car born from tragedy, through its numerous ups and downs, it is inarguably a treasure – and as far as we’re concerned, it’s as real an art car as any other. Burdened by a saddening history of the death of two of racing’s best, we can only hope the car continues to live on, celebrating the life of those who are responsible for its creation.